Intro: Why the auto industry presents significant investment opportunity

Why am I starting this substack?

Welcome to my Substack! You may know me as Forwardcap on Twitter, which has been a great channel to share my thoughts, but has limitations with its format. Here I’ll look to expand my scope and cover long-term investing broadly across the auto industry, specifically focusing on EVs and emerging technology. I think substack is a better platform to discuss long-term investing ideas/analysis and will maximize the quality of my posts and the overall reader experience.

There are 4 key reasons why this is an important industry for me to cover:

Automotive is a multi-trillion dollar industry, with only a handful of OEMs controlling most of the share, and is being disrupted from several angles. The passenger vehicle is likely to change more this decade than it has in the previous century, including how the vehicle is manufactured and operated (internal combustion engine vs electric motor), sold (direct vs dealerships), utilized (software and autonomy), and powered (charged vs fueled). This will transform the entire automotive value chain, and given the size of the industry, will likely result in more value-creation opportunities than almost any other sector over the coming decade. I also think true mass EV adoption and level-5 autonomous vehicles are several years away, so it’s still in the early innings, but change is happening quicker than it seems on the surface.

Along with the upside opportunity, this disruption will also result in significant risk and downside for many players. Some legacy OEMs will fail to adapt, and some startup OEMs will fail and/or never live up to their current valuations. Several startup OEMs with minimal lifetime production (i.e. Rivian and Lucid) have market caps rivaling established OEMs (i.e. Ford and GM), and many new technologies (i.e. QuantumScape and Aurora) have multi-billion market caps years before they expect to generate any material revenue. While I believe in the long-term upside potential, I’ve also been critical of the frothy valuations and grift throughout the space. There’s clearly a wide distribution of outcomes for many of these players and understanding the downside is critical for investors, whether you are looking for short exposure or simply looking to avoid bad investments.

Despite this massive opportunity for investors, this sector is significantly under-covered relative to other industries like SaaS, fintech, internet, crypto, and consumer. There’s a noticeable lack of investor interest in this industry, especially relative to its size and direct impact on everyday life. I believe this due to poor equity returns and lack of technology/innovation over the past several decades, but this is likely to change going forward.

I’ve gained valuable insights after covering automotive professionally, everything from OEMs to suppliers to dealers, in investment banking and to a lesser extent as a private equity generalist investor. I’ve also closely followed/invested in Tesla since 2015, which has been a great case study on the disruptive trends in the industry. I’m genuinely interested in writing about and investing in the automotive industry, which I believe is widely misunderstood.

While many investors may not see the upside opportunity in the industry, today’s leading technology companies seem to disagree. Apple has been trying to develop its own car for almost a decade, Google/Alphabet has been developing Waymo for even longer, and Amazon has invested billions into its Rivian minority stake and outright acquisition of Zoox. The market opportunity for new car sales alone is larger than smartphones, digital advertising, and cloud computing combined – it just hasn’t been monetized effectively. This doesn’t even include the addressable market for used car sales or ancillary services like autonomy/ride sharing, software/infotainment, and insurance.

This all begs the question: What’s likely to change the industry dynamics going forward/why should investors start to pay attention? To answer this, you must first understand why the auto sector has such low margins and market caps relative to other industries in the first place. Are low margins a structural part of the industry or a result of poor business models? Why does the market ascribe such low (often single digit) earnings multiples?

The average investor will simply say these outcomes are due to capital intensity, competition, and cyclicality. Capital intensity alone isn’t a negative IF you can generate a high ROI. Competition can be tough, but any large market is highly competitive and companies can still succeed with strong product differentiation. Cyclicality does play a role in valuation, as investors like predictable/recurring cash flow, but this doesn’t tell the whole story.

Here are my top reasons for why legacy OEMs have structurally low margins and the market values those earnings at a discount:

Outsourced distribution via independent dealers minimizes the addressable market opportunity and profit margins. For new car sales, dealers take a 7-13% cut of every car sold and mostly eliminate the OEM from any revenue stream (i.e. service and maintenance) post-sale. For context, Ford CEO Jim Farley estimates that dealers add $3-4k in distribution costs per car. For used car sales, outsourced distribution has a much larger impact, as legacy OEMs have minimal exposure to the massive used car market. If somebody is selling a car they own, it’s likely done through a 3rd party website (i.e. Carvana) or dealer, while dealers also handle most used sales of previously leased cars. OEMs are not really part of the equation and don’t own the customer relationship. Lastly, dealers add significant friction and time to the buying experience, which hurts demand.

Core ICE business (~100% of profit) is in secular decline and electric vehicles (“EVs”) will negatively impact profitability. EVs require significant upfront investment while also generating worse unit economics. Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares estimates EVs cost 50% more to produce than internal combustion engine (“ICE”) cars. This is a key reason why multiple legacy OEMs have been actively pushing to stop the transition to EVs. Declining ICE share will also cause ICE re-sale values to decline, which will negatively impact consumer demand and ultimately hurt ICE selling prices. At scale, EVs will eventually be cheaper to produce, but you first need to achieve volume production. This will be painfully difficult and some OEMs (both legacy and startup) won’t survive long enough to reach this milestone.

Producing EVs is vastly different from ICE cars and transitioning is very risky. Legacy OEMs’ core competency is manufacturing internal combustion engines, as most of the remaining components are outsourced. Of course, this skill is irrelevant for EV production. Additionally, EV manufacturing requires several new skills that legacy OEMs have minimal experience in (raw materials supply, cell to pack integration, battery management systems, etc). Two recent examples help illustrate this point: GM had to fully halt production of the Chevy Bolt from Nov’21 – Apr’22 because of battery issues, while Ford just ordered dealers to immediately stop selling the Mach-E because of battery issues (the timeline to resume sales is unknown). These are not typical recalls, but full production/sales halts that don’t happen with ICE vehicles.

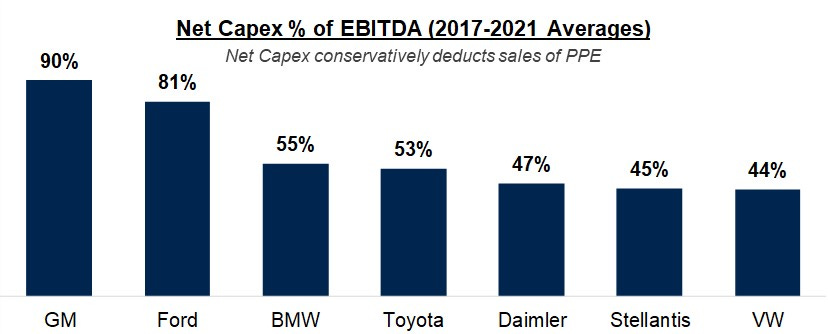

High maintenance capex/fixed costs and low ROIC limit long-term profitability. Despite negative growth highlighted below, capex remains very high relative to operating profits due to maintenance requirements for aging production facilities. Since 2017, the average legacy OEM spent ~60% of EBITDA on capex, despite minimal capacity expansion or product innovation, resulting in very low free cash flow conversion. Low return on incremental invested capital and a high fixed cost structure limits long-term profitability, even before considering lower margins on EVs going forward.

Zero/negative volume growth with uncertain unit growth going forward. Since 2017, large legacy OEM volumes have declined every year for a total of -21%. Going forward, supply chain normalization will drive near-term growth. However, long-term volumes are highly uncertain since their ICE products (over 95% of current sales, on average) are being cannibalized by new EV models, which results in minimal/zero incremental volumes. Additionally, there’s now competition from new market entrants for the first time in 70+ years. Before Tesla, there had been no successful mass-market OEMs since Jeep in 1941. It’s uncertain whether legacy OEMs will ever recover to pre-Covid volumes, and if they do, it’s likely not by much. Equity markets hate uncertainty and poor top-line growth prospects.

Outsourced supply chain increases production costs and dependence on 3rd parties while reducing product differentiation. Besides the internal combustion engine, legacy OEMs outsource almost every component of the vehicle (software, batteries, drivetrain, transmissions, seats, braking systems, etc). Without the internal combustion engine, legacy OEMs are not adding much value, which limits their potential to expand profit margins. It’s also harder to differentiate your product when it’s largely comprised of the same components/software from the same 3rd party suppliers as every other OEM. Depending on so many 3rd parties also makes it very difficult to adapt to changes in the market. OEMs can only move as fast as their suppliers, which largely prohibits significant product innovation/iteration. Software specifically is becoming an increasingly important aspect of the vehicle and almost every legacy OEM outsources their operating systems entirely. This significantly limits their ability to collect data (i.e. mapping, telematics) and monetize software and driver-assist features.

Workforces aren’t suited for a rapidly changing market environment. The major shifts in the industry (electrification, software, autonomy) require significant innovation, and legacy OEMs lack the necessary top engineering talent to adapt and execute. Various US surveys don’t include legacy OEMs in the top 10 most attractive employers for prospective engineering talent. Legacy OEMs are not founder-led and management teams are short-sighted given their incentive structures, which are largely based on near-term profitability. Non-executive employees have relatively low compensation and limited access to stock options, so most employees have zero skin in the game. The workforce also has liabilities (i.e. union and pension obligations, ICE production skill set) that negatively impact innovation and valuation.

Contrary to popular belief, the issues that limit market values of legacy auto OEMs are not structural to the industry, but mostly a result of their outdated business models and lack of product differentiation.

This has been my thesis for many years and Tesla is beginning to prove that a modern, fully integrated business model can extract significantly more value than peers. Tesla already has the highest operating margins in the industry and currently generates ~3x more operating profit (even excluding regulatory credits) per vehicle compared to average legacy OEM, despite many headwinds (higher cost to provide EVs, smaller scale, inability to sell cars in 10 states, etc).

As a result, many OEMs are now trying to shift their business models by removing dealers, switching to an online sales model, and separating ICE and EV businesses into separate divisions, which will present significant challenges but also opportunities. Add in startup OEMs and technologies with massive market valuations but minimal revenue, and it’s clear there’s a very wide range of potential outcomes for the entire ecosystem that investors can take advantage of. I look forward to covering all of the developments as they play out over the coming years.

If you’ve made it this far, please consider subscribing and feel free to provide feedback! Thanks for reading.

Great article, indeed. Thanks a lot!

I am wondering about your statement that low valuation is not a structural issue. However, I see high Capex needs as the primary constraint for cash flow generation and share price appreciation. What changes do you see in this respect? How could OEMs decrease their Capex needs? Looking at such start-up companies as Lucid and Rivian, they both have a large cash burn due to Capex. Arrival tries to present a CAPEX-light model but does not seem successful so far. I would appreciate your view.

I wonder if future installments will consider the effect of the Oil industry on the economic dynamic for the legacy auto transitioning to EVs?

I perceive a lot of foot dragging and whistling past the grave yard in the lack of urgency of Legacy Auto's EV transition and I wonder if economic pressure plus old boy network rib nudging can be documented.

After all if the legacy OEM successfully convert their products to EVs they still have a business but Oil companies stand to loose up to 2/3 of their market.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/use-of-oil.php