Do legacy OEMs really want to sell EVs?

Analyzing how legacy OEMs view EVs and why

I write about investing in electric vehicles and new technology in the auto sector. This includes industry and equity writeups like this, plus a weekly news analysis. If you find this post interesting, please consider subscribing! It’s 100% free.

This will have two sections: How do legacy OEMs view EVs? Why is this the case? The first question may sound dumb given legacy OEM investments in EV infrastructure, production, and advertising, but the facts tell a different story.

How do legacy OEMs view EVs?

Let’s start from the beginning – electric cars are not a new invention and were initially introduced in the 1800s. Due to higher costs and inefficient battery technology at the time, EVs were dismissed with the introduction of internal combustion engine (“ICE”) cars in the early 1900s.

Fast forward to the 1990s. General Motors pioneered the first purpose-designed, modern EV from a major automaker with the EV1. Customers loved the product and GM demonstrated the vast improvements in modern battery technology. However, despite overwhelmingly positive customer feedback, GM discontinued the program in 2002 because EVs were an unprofitable and niche part of the market. In addition to stopping production, every EV1 was taken back by the company, despite significant protests from customers, and most were subsequently crushed in a scrap yard.

This situation is bizarre. GM abruptly killed the EV1 despite knowing they were relinquishing a potentially strong first mover advantage in the EV space. GM self-sabotaging its EV program, while physically crushing and ensuring the cars were never used again, was the first sign that automakers want to maintain the status quo. You can learn more in the 2006 movie Who Killed the Electric Car?

For years after the EV1 debacle, most OEMs completely dismissed the idea that EVs can be viable at scale. Automakers claimed the technology was too expensive, inefficient, dangerous, and not desirable from a consumer perspective. Since then, battery costs have declined dramatically and these rest of these perceived issues have been proven untrue. Still, many OEMs still don’t welcome the transition to EVs.

Let’s take Toyota for example, the largest OEM by volume today at ~10M units annually. Toyota continues to lobby against EVs and invest in new ICE vehicles and manufacturing plants, while producing its first fully-electric vehicle, the bZ4X, just this year. For what it’s worth, that launch has been a disaster.

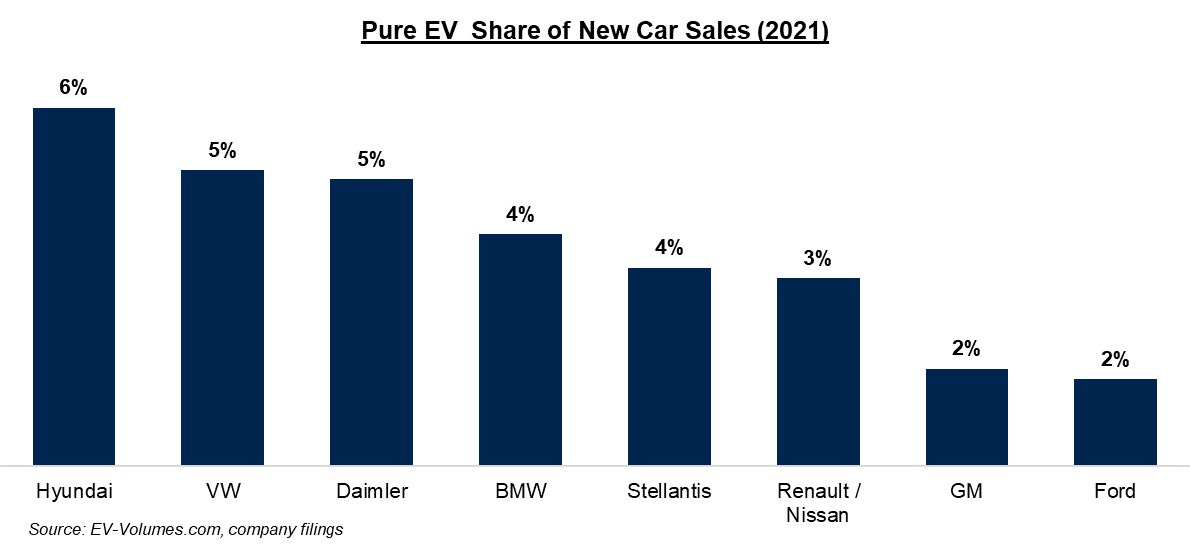

While other automakers are way ahead of Toyota, EV share of new car sales is still only ~4% for other legacy OEMs, on average. Even the most forward-thinking automakers have also lobbied for weaker fuel standards and admit that EVs won’t account for a majority of sales until at least 2030.

While this transition seems to be happening very suddenly, it’s not breaking news that EVs are great and desirable products. In fact, the Model S was named MotorTrend’s 2013 Car of the Year (and subsequently named the best car they've ever tested in 70 years) in addition to being named Car & Driver’s Car of the Century in 2015. Tesla even open sourced its patents in 2014, yet automakers have been very slow to act.

Another piece of evidence highlighting automakers’ opposition to EVs is the overall product presentation. Instead having household names like the Camry, many EVs have strange names that are difficult to remember. Like the aforementioned bZ4X - what kind of name is that? On top of that, the designs are objectively odd. With these designs, there was never any chance that these EVs would have strong mass appeal. The examples below may seem cherry-picked, but these are actually the top selling EVs of all-time for the BMW, Chevy, Nissan, and Renault brands! All of these companies have made great-looking cars before, but chose not to for their EVs. There’s no reason why EVs can’t just look like regular cars.

While recent EVs have significantly improved designs and naming conventions (i.e. F-150 Lighting), there was a long period where EV sales were deliberately undermined.

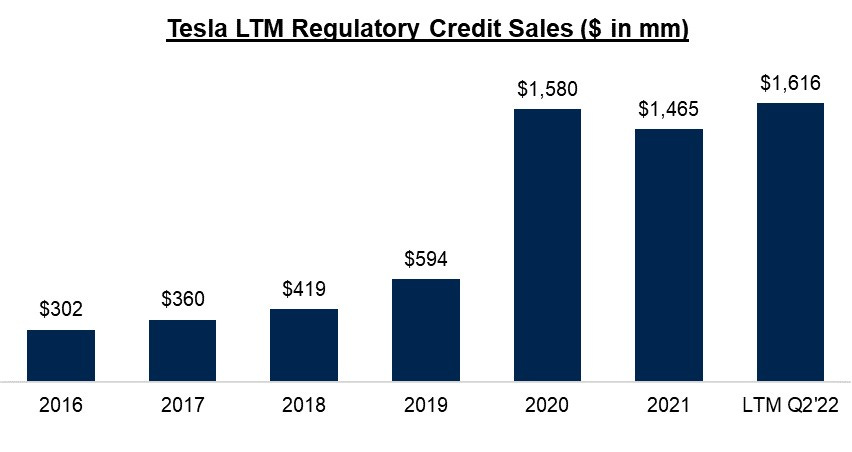

The last area I’ll cover is regulatory credits. While the emissions standards are mandated by governments, the credit sales are actually from other OEMs. Think about that for a moment. Legacy OEMs have had many years to make compelling EVs, with the help of Tesla’s open-source patents, but instead chose to pay cash penalties to their competitor. Tesla no longer relies on these credits for profitability, as credit sales accounted for just 17% of operating profit in H1’22, but these credit sales definitely helped Tesla grow to become a formidable competitor.

While regulations have been and will continue to get stricter, many OEMs are failing to meet emissions standards simply because their EVs don’t make a material impact. For example, Mazda released its first EV last year, the MX-30, which has only 100 miles of range. With that fact alone, you’d probably guess that not that many people want this car, and you’d be right. Mazda has only sold 500 lifetime units and sold just 8 units in July 2022.

While credit sales should decline from here, it’s notable that OEMs have been paying cash penalties to a competitor instead of just producing compelling EVs themselves.

Why do legacy OEMs oppose EV adoption?

Some automakers have stronger feelings towards EVs than others, but it’s clear the industry worked had to avoid the transition away from ICE. The next question is why? I'll summarize 5 reasons: lower ICE residual values, dealer conflicts of interest, higher EV production costs, owner and management incentives, and different skillsets.

Lower ICE residual values

Legacy OEMs have large financing divisions that rely on residual values of ICE vehicles. Higher residual values also improve consumer demand for both leased vehicles (more affordable leasing rates) and owned vehicles (lower depreciation).

Rising EV adoption will put significant downward pressure on ICE residual values, which negatively impacts both profitability and customer demand for ICE cars. The transition to EVs will shift consumer preferences, supply chains, fueling networks, and economies of scale away from ICE and towards EVs. It will become increasingly more expensive to produce and sell ICE vehicles, while consumer demand dwindles and EVs become more affordable. That’s a deadly combination for ICE residual values.

Additionally, preliminary data suggests that EVs have higher residual values and stronger value propositions than ICE vehicles. Hertz just highlighted that EVs require ~50% less maintenance, have lower depreciation, and generate higher satisfaction scores than ICE. This doesn’t even account for the fuel savings. As both consumers and companies realize the benefits of EVs, automakers will be negatively impacted by lower residual values on existing fleets.

Dealer conflicts of interest

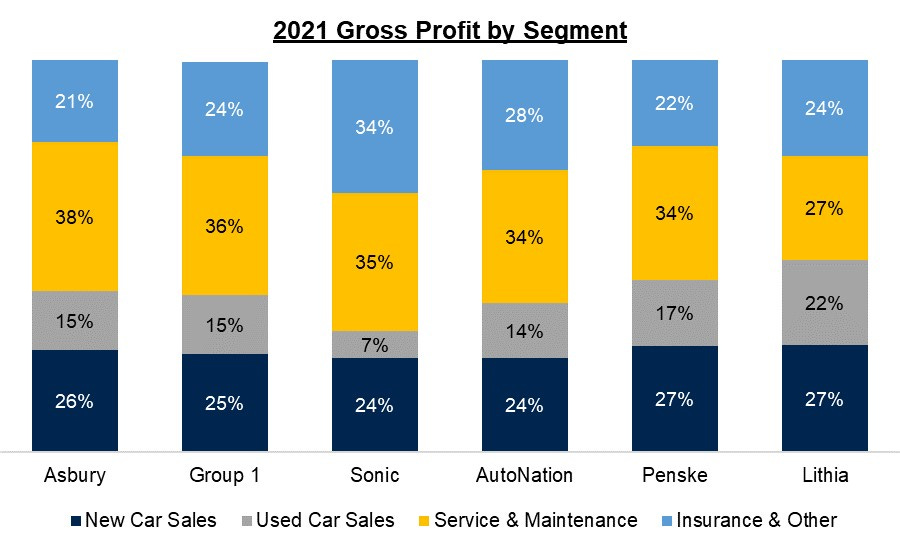

Another key reason why OEMs are hesitant to produce EVs is because dealers themselves don’t want to sell them. On average, public dealers made 34% of FY21 gross profit last year from service and maintenance, more than any other segment. This share of profits is actually much lower than the industry average since the smaller operators don’t have sufficient scale to make the same margin on vehicle sales.

This is an issue because EVs require significantly less maintenance (i.e. no oil and transmission fluid changes, fewer parts, lower brake and motor degradation). Used car profitability is also at risk due to the likely decline in ICE residual values, also caused by EVs. As a result, dealers have implemented tactics that hurt the auto brands they represent, including significant dealer markups (sometimes as high as 50%) and losing the car keys, all so that customers will buy an ICE vehicle instead.

I’m not surprised that OEMs are reluctant to produce EVs when their dealers go out of their way to sabotage the products.

Higher EV production costs

Until OEMs reach significantly higher volumes, EVs are more expensive to produce. In fact, the CEO of Stellantis estimates that EVs cost 50% more than a comparable ICE vehicle. Another example is Ford, who still sells EVs at a loss today despite the benefit of a $7,500 U.S. tax credit that key competitors (Tesla and GM) don’t have.

This higher cost of new production, combined with lower residual values for the existing fleet, will put significant downward pressure on profit margins. OEMs already have razor thin profit margins that will decline further with higher EV adoption, hence the opposition against transitioning away from ICE.

Owner and management incentives

Developing a successful EV platform requires significant risk, long-term thinking, and group cohesiveness. This is very difficult to accomplish when different stakeholders, namely legacy family shareholders, are risk averse and want to preserve profitability. Legacy families still have significant influence across many OEMs:

The Porsche-Piech family controls the majority of Volkswagen’s voting rights

The Quandt family controls the majority of BMW’s voting rights

The Toyoda family largely controls Toyota through a complex cross-ownership and board control structure

The Ford family controls 40% of Ford’s voting rights

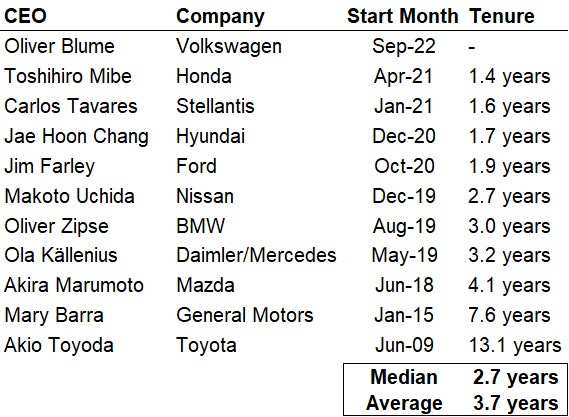

In addition to shareholder misalignment, EVs haven’t gained much traction internally because of high executive turnover. Legacy OEMs have struggled to maintain management continuity for more than a few years.

This dynamic makes it very difficult to execute a transition to EVs, which requires a consistent long-term strategy. Management teams are also largely incentivized by profitability targets, which also hinders their ability to aggressively pursue EVs.

Different skillsets

Besides the internal combustion engine, legacy OEMs outsource almost every component of the vehicle. EV production renders this skillset irrelevant and also introduces new challenges that these OEMs have no experience in, including raw materials supply, cell to pack integration, and battery management systems. This difficulty has been proven several times, including GM halting the production of the Bolt for 6 months due to battery issues. Securing the raw materials alone is difficult and takes a long time to accomplish.

Additionally, it takes time to retrain and right-size the existing workforce. Just a few weeks ago, Ford announced it was laying off 8,000 workers related to ICE operations but still needs to hire thousands of EV-related positions. Layoffs are difficult for any company or management team, but especially for auto OEMs given the strong union presence.

EVs force OEMs to stray away from their core competencies, which adds complexity and difficulty.

Conclusion

Don’t let the EV marketing campaigns fool you – automakers have tried to prolong EV adoption as long as possible but can no longer ignore this existential threat. Of course, every OEM would love to be producing millions of EVs today but the path to get there is extremely expensive and difficult. The number of different stakeholders (i.e. dealers, unions, legacy family shareholders) will amplify these challenges.

While many new, pure EV OEMs have even bigger challenges to overcome, these startups do have certain structural advantages over legacy automakers. I look forward to covering the EV transition as it plays out over many years.

If you’ve made it this far, please consider subscribing! In addition to industry and equity write ups, I also post a weekly news analysis. Everything is 100% free.

I just recently follow you, and you are worth every minute of it. You have a deep understanding of the subject matters (EVs and Tesla!). Great fact driven piece on the past and present of LICE, they are so fked. I look forward to read more article from you in the future. May I suggest you get involve with the Tesla communities (Dave Lee on investing, Rob Mauer, teslamotorsclub.com etc) so that you guys can compare/share notes, debate etc.